Video games are a severely misunderstood media. Often written off as an addictive escape-fantasy for lonely nerds at best or demonized as a motivator for violence at worst, gamers frequently and unfairly find themselves in the difficult position of having to justify this hobby as if games are some kind of symptom of psychosis or immaturity.

On the other hand, casual games are becoming more common and accessible thanks to the prevalence of smartphones and tablets. I would hope that the cliche of the pale, socially-awkward gamer had begun to fade, but it’s still as popular as it ever was. Despite everyone’s grandmother playing Candy Crush or Farmville nowadays, not many people would argue that games serve a higher purpose other than mindless entertainment and fewer still would declare that they can actually teach us anything.

It probably won’t surprise anyone to find out that I’m about to do exactly those two things. And even though I’d love to rush to the defense of games by citing numerous instances when movies and TV have glorified violence in worse ways than games have or by discussing other addictive media-based escape-fantasies that non-gamers are prone to (*ahem* Facebook), I would rather contend that behind the simulated zombie slaying are valuable lessons to be learned, that the positive and constructive experiences consistently found in games far outweigh the negative ones.

My own childhood abounded with such experiences, and although not every game enriched my little sponge-like brain, here are five examples of specific games I played that I believe prepared me in some way for the journey of musicianship. I should note that I am not a neurologist or game designer and that there is no specific scientific research behind these particular claims. These are all my own personal accounts and the conclusions I draw are entirely my own. If you want a real scientist’s word, here are a few things you should read.

1. The Legend of Zelda taught me that learning is a challenge and challenges can be overcome.

For those of you who have never played a game, allow me to sum up the basic premise of 98% of video games: You play as hero of some sort (fighter pilot, mysterious warrior, vaguely ethnic plumber) with some kind of quest to accomplish (save the princess, slay the dragon, blow up the Death Star). You have a set of skills you become familiar with through a tutorial or the trial and error of pushing buttons. Usually you will unlock or discover new skills that help you through various stages and challenges until said quest is accomplished.

Sound analogous to learning an instrument? Shoot, replace “save the princess” with “play Für Elise” and it’s practically identical to piano lessons, even down to the button-pushing part.

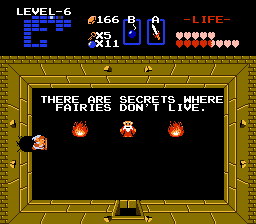

Personally, this hero-on-a-quest mentality prevalent in most games really primed my brain for the challenge of making music. No game illustrates this more beautifully than The Legend of Zelda on NES. For starters, this game’s quest is a double-whammy: you save the princess by slaying dragons and other mythical beasties.

Monster destruction wasn’t even the challenging part, though. You had to find your way through elaborate labyrinths complete with traps, locked doors, and secret passageways. You usually had to locate a map, compass, and a specific tool hidden before parts of the dungeon were even accessible. Even after you found your way to the end and slew the head beastie, there were no specific instructions on where in the vast world to continue the quest, save for the occasional vague riddle.

Beating games like this is a matter of grit, or at least it was in the pre-internet days. You couldn’t just look up the answer; you had to explore or experiment your way to a solution which always takes a good deal of resolve. Also, nothing feels as good as the moment you realize one of your crazy ideas worked.

Zelda helped me realize that challenges are often just a matter of having the right tools and figuring out how to use them. In music, viewing obstacles this way made a huge difference in my determination to learn music I love. After all I went through to save the princess, it actually seems pretty easy by comparison.

2. Diablo taught me to try, try again…and when that doesn’t work, try something else.

Perseverance alone won’t win the day. For example, when slaying that dragon: if the battle axe fails over and over, why keep trying it? Rethink your strategy instead. Perhaps a different weapon? Maybe get your armor dragon-proofed? Really good games offer multiple paths to success and reward you for thinking outside the box. Maybe you’ll find out the dragon is just misunderstood and actually quite reasonable when engaged in rational conversation.

Games encourage us to look at problems from different angles, to consider multiple paths to achieve our goals. Challenges get more difficult as the game progresses and your success hinges on how wisely you use your skills. Your ability to problem solve and make adjustments to your play style determines the level of your success.

One of my favorite examples of this is my battle with the Butcher in Diablo, a PC game with only two objectives: slay bad guys and get loot. It’s a tried-and-true formula that endures even to this day.

The first really tough baddie you face in Diablo is The Butcher. One might expect a creature with such a diabolical name to look something like this:

…and one would be correct.

The Butcher is a pretty early fight in Diablo, meaning there wasn’t a lot of time to improve my skills or find better weapons and armor before I had to face him. He, on the other had, has a massive cleaver and…well, an apron, but trust me, he’s a tough cookie. Much like the aforementioned dragon, charging right at him did not end well. At my wits end, I resorted to looking up a more clever solution in a guidebook for the game.

I wish I was clever enough to think of it myself because this strategy was sheer genius. All I had to do was lure him to a corridor where I could slam a door in his face but still see him through a metal grate (apparently he’s not that bright). From there, I used a trusty bow and about a hundred arrows to chip away at his health through the grate until he dropped.

It wasn’t honorable or heroic but I didn’t care. I got to use his shiny cleaver after that! At the end of the day, I found a strategy that allowed me to achieve what I wanted to achieve. There are no rules and no “right” way to do this.

Tackling a musical challenge is no different. Ask yourself, “What am I doing differently this week?” If the answer is “Nothing,” then it’s time to brainstorm different ways to practice. Often it comes down to working on a single aspect of a particular skill, like coordination or timing. Find something that works for you and move on. (Bonus lesson: Don’t be afraid or ashamed to ask for help).

3. Rebel Assault taught me to admit I needed to dumb down the difficulty.

Many games feature varying levels of difficulty for players, something along the lines of Easy, Normal, Hard, and occasionally a super-challenging mode called Expert or Soul-Crushing or something of the like. For most games, this is an important feature as the learning curve of one game may be much steeper than another. It’s often a good idea to try the easy mode while you learn the mechanics of the game before trying the more difficult modes (a lesson I learned the hard way more than once).

Music has it’s own difficulty level, and I don’t just meant the literal one printed on many books (beginner, intermediate, etc). There exists another difficulty level, and it’s a self-imposed one: the tempo (speed) which you attempt to play. Precision comes with slow and deliberate practice, but who has the patience for that? You want to play this song now. It’s the same impatience that tricks you into thinking you can reach your fitness goals with more effort at the gym.

Learning to admit when I can’t play something at full speed and pace myself took quite a bit of humility. Fortunately, I got some practice from an ancient CD-ROM game called Rebel Assault in which I played as a rookie pilot in the Star Wars universe. I certainly felt like a rookie because I couldn’t get past the initial training mission. This was the first time I used a joystick as opposed to a handheld controller and I remember experiencing terrible frustration as I watched my star-fighter explode again and again.

Still, I wanted–no needed to improve; the fate of the Rebellion hung in the balance after all. But I just couldn’t do it. Fortunately, the game had an easy mode which apparently reinforced my fragile ship with a stronger alloy or something so it wouldn’t blow up so readily. I was able to get used to the joystick and develop the skills I needed to save the galaxy (eat your heart out, Skywalker). None of it would have been possible if I hadn’t just slowed things down for myself and the same has proven true for countless piano pieces I’ve learned.

4. Double Dragon 2 taught me that repetition is the key to improving your skills.

All skills are basically the same. You’ll need those 10,000 hours of practice regardless of what it is you want to master. Double Dragon 2 on the NES taught me this harsh reality by introducing me to the Cyclone-Kick, a deadly move I initially discovered completely on accident.

That probably bears some explanation: In DD2, you (and a friend if you had one handy) had to go beat up some bad guys. I don’t really remember why…they may have kidnapped your girlfriend or something. It’s not really important. What is important is mastering the Cyclone-Kick.

Now this will shock the younger gamers out there, but game controllers on the NES used to only have two buttons. In brawler games like DD2, this usually meant one button punched and the other kicked. You could jump, but you had to press both buttons simultaneously to do so and the game was unforgiving about the timing.

To perform the legendary cyclone kick required jumping, then moving in lateral direction while simultaneously pressing the kick button once the avatar had reached the pinnacle of the jump. Again, I can’t stress how precise the game demanded these steps be. At this point in my life, the Cyclone-Kick was the most complex execution of motor skills I had ever attempted and I include the three years of piano lessons preceding it.

Needless to say, I toiled away learning this move. It was just too satisfying to watch foes flying away from me as I spun wildly through the air like a little Nintendo tornado. A Nintenado? You have no idea how difficult that just was for me to spell. In any case, dibs on that if it’s not already someone’s Twitter handle. (I checked: it is).

I won’t go so far as to say that I applied the same tenacity to my musical study, but I have no doubt that practicing this very specific thing made me a lot more conscious of the concept of timing as well as the subtle nuances a split second’s difference can create. It’s an ability any musician needs to deeply embed in their subconscious, so why not get some extra practice by kicking some bad guys in the face?

The bottom line: repetition helps you learn. Even having someone tell you the same idea twice but phrasing it in a slightly different way can be useful in the pursuit of knowledge. That’s because repetition helps you learn.

5. Mario Kart 64 taught me that if you got it, flaunt it.

Do anything for long enough and you’ll become pretty good at it. But then what? What’s it all for? I’m not sure how to answer that other than I suppose it depends on the skill we’re talking about. If that skill happens to be a video game, though, there is only one answer: pwn your friends.

The only game I ever reached that level of mastery in was an older version of the popular racing franchise Mariokart for the Nintendo 64. For at least a six month period, I was nearly unbeatable. My reputation was reinforced in many a basement as I would thrash my friends with considerable consistency.

I’ve always been a competitive person, but I also used to be extremely shy. I used to go out of my way to avoid attention from other people, even positive attention. It’s funny to think of my friends hearing this normally quiet person cackling with mad delight as he trashed them for the fifth time in a row. It felt so good to hear my friends admit, even grudgingly, that I was good at this.

I’m not advocating arrogance or bad sportsmanship, but something that you might not understand if you’re not or never were a shy person is how tempting it can be to hold yourself back from other people. Avoiding the spotlight allows you to hide your failures from other people and even though it also conceals your success, some of us would rather have the safety of just feeling like a “normal” person.

There’s nothing wrong with keeping to yourself, but there’s a difference between that and hiding from the world out of irrational fear. With music, it’s nearly impossible to behave like this and survive, but I’ll admit I’ve been guilty of crossing that line. I’ve refused to play the piano at a party because I didn’t want to seem like a show-off or talked myself out of entering a song-writing contest or going to an open-mic night because I worried people wouldn’t like my music or my haircut or just me as a person. I know it’s silly, but it’s the kind of thing that keeps a lot of good musicians, artists, writers, poets, and other creatives down.

To be honest, this is the lesson I’m still learning, but I feel like I’m slowly but surely progressing. Not unlike my superb Kart-Kontrol and deadly precision with a green shell, it’s just a matter of time and patience.

Leave a Reply